by the Editors at Black Belt

BRUCE LEE is a registered trademark of Bruce Lee Enterprises LLC. The Bruce Lee name, image and likeness are intellectual property of Bruce Lee Enterprises LLC. – August 12, 2013

Bak mei (white eyebrow) kung fu master Leung Sheung proudly demonstrated another self-defense technique to his class: side kick, grab, punch. Leung Sheung executed the movements with as much fluency and precision as would be expected from any 20-year veteran of the fighting arts. The students then imitated the perfection of his form. In the back of the room, the old man quickly turned his head away and bit down on his tongue, swallowing his laughter.

Side kick! Grab! Punch! The old man leaned against the wall for support. Now his body shuddered as he struggled to conceal his amusement. Suddenly, his efforts failed, and his silent chuckles grew into loud roars of laughter.

Download 7 FREE Bruce Lee E-Books!

The FREE Bruce Lee E-Book Collection

Leung Sheung stopped his class, his face red with anger. “Hey, old man!” he snapped. “What are you laughing at?”

“Oh, nothing,” he replied. “Please continue. I’ll try not to disturb you further.”

Leung Sheung took a deep breath and paced across the room. He was still furious. “Look, old man, a few months ago we found you living out of garbage cans in Macao,” he said. “We brought you here to the Union Hall. We gave you a place to sleep and food to eat. The least you could do is show a little respect when I’m teaching.”

The old man perked up an ear. Had he heard the man say “respect”?

“Then the least you could do is show a little respect for the art that you teach,” the old man growled back. “All you do is have your students punch air.” He quickly moved through Leung Sheung’s technique: side kick, grab, punch. “But the air doesn’t hit back. What happens when you face an enemy who will?”

The old man shook his head. “If you are going to practice kung fu,” he said, “you should do so seriously — or not at all!”

“Look, old man,” bellowed master Leung Sheung, “if you think you know something, why don’t you come up here and teach me?”

With this challenge from Leung Sheung on that day in 1952, Yip Man officially opened the doors on his 20-year career as a martial arts instructor and patriarch of wing chun. Standing only 5 feet tall and weighing 120 pounds, Yip Man proceeded to throw the 6-foot, 200-pound bak mei master around the room with almost no effort. No matter how Leung Sheung attacked, he always found himself carefully deposited on the floor.

When all was said and done, Leung Sheung had surrendered his kung fu class at the Restaurant Workers’ Union Hall to Yip Man and had become Yip Man’s first disciple.

The Master’s Past

Yip Man did not happily accept his new role in life. Before World War II, he had been a member of a wealthy merchant family in the southern Chinese town of Fatshan, in Kwangtung province. He had owned a large manor house, a prosperous business and a farm, and he had enjoyed a life of relative ease with his wife and family.

Between 1937 and 1941, Yip Man served in the army during China’s valiant effort to repel the Japanese invasion. He returned to his family in Fatshan during the years of the Japanese occupation. Times were hard. His farm was ruined, and his wife became ill.

The end of the war brought little improvement. China needed to rebuild its ravaged cities and towns but found itself embroiled in civil war instead. The nationalist Chinese government recruited Yip Man to the post of captain of the police patrols for Namhoi County. Although the government appointment helped the living conditions of the Yip Man homestead, it did not come in time to prevent the death of Yip Man’s wife from extended illness.

After the Communist triumph in 1949, Yip Man left his two grown sons in Fatshan and fled to Hong Kong. If he had remained, his position as police captain would have meant almost certain death at the hands of the Communists. Thus, at the age of 51, Yip Man was forced to start an entirely new life from scratch.

“When the Communists took over, he lost all his major tangible assets,” explains William Cheung, one of Yip Man’s most senior disciples. “But he still had whatever he could carry: money, gold bars, etc. But Fatshan was a very small town compared with Hong Kong and Macao. There were a lot of shrewd operators in the city. So he immediately lost some of his money through people cheating him.

“Then the heartbreak of losing his home and his wife and being separated from his family caught up with him. He became disillusioned and perhaps began to pity himself. Soon, the Chinese nobleman found himself destitute.

“Then Leung Sheung and a chap called Cheng Kao found him wandering around at the pier of Macao. He seemed to be homeless. They didn’t know that he was a martial artist. They were just being kind. They would have helped anyone they could. So they took him back to the premises of the Restaurant Workers’ Union Hall. They let him stay there. When Yip Man started teaching at the Restaurant Union, he first taught Leung Sheung, Lok Yiu and Cheng Kao. Then there were a few others, like Tsui Sung Ting. Of course, Leung Sheung, being a kung fu master already before he studied wing chun, progressed much faster than the rest.

“A few months later, the rest of us turned up.”

Yip Man quickly proved to be a most unusual instructor. For example, William Cheung recalls that during the seven years he spent with his teacher, he never once saw Yip Man actually teach a wing chun class. Yip Man was usually present in the back of the room, supervising the assistant instructors and correcting his favorite students, but the actual tasks of instruction were left to Leung Sheung, Lok Yiu, Tsui Sung Ting, Wong Shun Leung and William Cheung.

Take your wing chun training to the next level

with William Cheung and his disciple, Eric Oram, in this FREE download!

10 Wing Chun Kung Fu Training Principles Any Martial Artist Can Use

“He never taught classes himself,” William Cheung says. “Well, only in some situations … with the big clients, the ones who could pay very heavily for a private session. At those times, he would often take me along. Then, suppose he was going to teach a wooden-dummy technique, he would show the technique once. After that, I would help the person.” Yip Man’s regular classes generally consisted of forms practice, chi sao (trapping hands) drills, wooden-dummy techniques and free sparring. There was no set pattern to the sessions. Each assistant instructor was allowed to exercise some personal discretion.

At rare times, the grandmaster might touch hands with one of his favorite students in chi sao practice. But those occasions would last only for a few seconds at a time. Yip Man feared that by doing chi sao with a junior, his own technique would deteriorate. He would have to slow down to create openings for him.

Yip Man had a soft-spoken style that taught more by example and suggestion than by the spoken word. He urged his students not to bully people or to act in a rude or arrogant manner. And he tried to keep them from fighting in the street gangs of Hong Kong, though he did encourage organized competition.

Bruce Lee’s Memories

In Bruce Lee: The Man Only I Knew (Warner Books, 1975), Linda Lee Cadwell quotes from an essay written by her husband, Bruce Lee, for freshman English in 1961. The essay clearly illustrates the subtle tactics Yip Man would use to influence his students:

“After four years of hard training in the art of gung fu (kung fu), I began to understand and felt the principle of gentleness — the art of neutralizing the effect of the opponent’s effort and minimizing expenditure of one’s energy. All this must be done in calmness and without striving. It sounded simple, but in actual application it was difficult. The moment I engaged in combat with an opponent, my mind was completely perturbed and unstable. Especially after a series of exchanging blows and kicks, all my theory of gentleness was gone. My only thought left was somehow or another I must beat him and win.

“My instructor, Professor Yip Man, head of the wing chun school, would come up to me and say: ‘Relax and calm your mind. Forget about yourself and follow your opponent’s movement. Let your mind, the basic reality, do the countermovement without any interfering deliberation. Above all, learn the art of detachment.’

“That was it! I must relax. However, right here I had already done something contradictory, against my will. When I said I must relax, the demand for effort in ‘must’ was already inconsistent with the effortlessness in ‘relax.’ When my acute self-consciousness grew to what the psychologists call the ‘double-blind’ type, my instructor would again approach me and say: ‘Preserve yourself by following the natural bends of things and don’t interfere. Remember never to assert yourself against nature; never be in frontal opposition to any problem, but control it by swinging with it. Don’t practice this week. Go home and think about it.’

“The following week I stayed home. After spending many hours in meditation and practice, I gave up and went sailing alone in a junk. On the sea I thought of all my past training and got mad at myself and punched at the water. Right then at that moment, a thought suddenly struck me: Wasn’t this water, the very basic stuff, the essence of gung fu? Didn’t the common water illustrate to me the principle of gung fu? I struck it just now, but it did not suffer hurt. Again I stabbed it with all my might, yet it was not wounded. I then tried to grasp a handful of it but it was impossible. This water, the softest substance in the world, could fit itself into any container. Although it seemed weak, it could penetrate the hardest substance in the world. That was it! I wanted to be like the nature of water.”

Although Bruce Lee added a bit of his own genius to the events he related in this essay, it does indicate the intellectual as well as technical heights to which Yip Man inspired his students. But at the same time, the wing chun grandmaster also had a playful streak. He loved Bruce Lee’s practical jokes — which was probably tough to do when he would show up for class with itching powder, handshake vibrators and water-squirting cameras.

“Yip Man had a very good sense of humor,” William Cheung says. “He liked to give his students nicknames, and he would take a long time to dream them up. Like Wong Shun Leung was called ‘Wong Ching Leung,’ which means that he’s like a bull. I was called ‘Big Husky Boy.’ And Bruce was nicknamed ‘Upstart.’”

Two years after Yip Man began teaching at the Restaurant Workers’ Union Hall, he was asked to leave. His classes had grown so large and included so many nonunion members that the hall had actually become a kung fu school. So Yip Man and his followers opened the first commercial wing chun school on Lei Dat Street in the Yaumatei District of Kowloon.

Although Yip Man was now a self-supporting member of society with a successful business, his life was still not a happy one.

“He remarried in 1954,” William Cheung says. “He was about 56, and she was about 40. He met her in a restaurant, I think. Anyway, some people thought she didn’t have a very clean past. All his students sort of looked down at her, and this made Yip Man very upset.

“People do not realize that life changes. It moves in cycles. Sometimes it progresses, sometimes it transcends. So there are times that you have to forget about the past. The students were very narrow-minded. They just didn’t show any respect for their master. They even used to address him as ‘old man’ sometimes in a very disrespectful way.

“This was one of the reasons Yip Man never taught a class personally. And I don’t think he was doing the wrong thing by not teaching. Only after the fame of Bruce Lee did they realize that the master was so great and that the style was so great because they saw that it could produce practitioners like Bruce.”

According to William Cheung, Yip Man’s difficulties with his students were further aggravated by his continued drug use. Sometimes the school rent would go unpaid. By 1956 Yip Man had been evicted from his first school in Yaumatei.

The wing chun clan then moved to an apartment in a government-supported housing project, where Yip Man lived and taught. His students formed a committee that collected the school tuition, paid the rent and left Yip Man with a living allowance.

William Cheung recalls that during this period, his master would sometimes have to fight for survival — literally. “At the time we moved to the government house, there was a restriction on water,” he says.

“They only turned on the water once every four days for four hours,” William Cheung recalls, “so you had to collect buckets of water to store until the next four days were over.

“Usually I did all the chores and organization around the apartment, but that morning, I was at the market and my master wanted to get some water. Now all the tenants had to get their water from the same government tap.

“The local gangsters got a hold of this tap and charged everybody 50 cents a bucket.

“Well, because it was so early in the morning, Yip Man didn’t have the humor to argue with these characters, so he challenged them.

“I had just gotten back to the apartment when I heard the commotion. I could see what was happening and I started running toward it. Yip Man was fighting at least six or seven. The thugs all had poles for carrying buckets. They probably used them to threaten people. Yip Man took away one of their poles, then he flattened them all within seconds. When I got there, they were all dragging their poles, holding their heads and running away.

“From then on, every morning — not just every four days, but every morning — two buckets of water were delivered to the apartment.”

As the years passed, Yip Man’s reputation as an instructor grew, and he was eventually able to afford better accommodations. In fact, by 1964 he was able to bring his two sons and their families out of mainland China. Three years later, due in part to the prosperity brought to him through Bruce Lee’s The Green Hornet fame, Yip Man made his final move to a large, well-equipped gymnasium.

Today, Yip Man’s martial arts legacy has been encased in mystery. Many wing chun instructors claim to be his direct disciple or the personal inheritor of some secret set of wing chun techniques. However, as William Cheung confirms, “Probably fewer than six people in the whole wing chun clan were personally taught, or even partly taught, by Yip Man. Yip Man had to teach the first two so that the first two could teach the next six.”

“But Yip Man was so intelligent in the martial arts that he could not stand a slow student,” William Cheung says. “He was very impatient with slow students. So he could not stand to teach more than a few. Also, he belonged to the old tradition, influenced by the Boxer Rebellion, which believed that the martial arts should not be passed on to Westerners. He even believed that wing chun should be just a household art.

“Yip Man was a well-educated man who never wanted to teach kung fu. His best loves were watching soccer and attending the Chinese opera. His strongest hatred was for ignorance. That’s why he did not like many martial artists. He was a man of perfection. He believed that there’s no halfway to doing anything.

“That’s why a lot of people did not understand him.”

In May 1970, Yip Man permanently closed the doors on his career as a martial arts instructor. He died from throat cancer on December 2, 1972. He was 79.

Permalink:

http://www.blackbeltmag.com/daily/traditional-martial-arts-training/wing-chun/yip-man-wing-chun-legend-and-bruce-lees-formal-teacher/

View the original article here

In the martial arts, one school of thought holds that you should change your game to match your opponent’s. Example: If you’re a stand-up fighter and you’re facing a grappler, you should immediately switch into grappling mode. Problem is, that requires you to train to such an extent that each subset of your skills is superior to the skills of a person who focuses on only that range of combat. Your grappling must be better than a grappler’s, your kicking must be better than a kicker’s and your punching must be better than a puncher’s. It’s a tough task, to be sure.

In the martial arts, one school of thought holds that you should change your game to match your opponent’s. Example: If you’re a stand-up fighter and you’re facing a grappler, you should immediately switch into grappling mode. Problem is, that requires you to train to such an extent that each subset of your skills is superior to the skills of a person who focuses on only that range of combat. Your grappling must be better than a grappler’s, your kicking must be better than a kicker’s and your punching must be better than a puncher’s. It’s a tough task, to be sure.

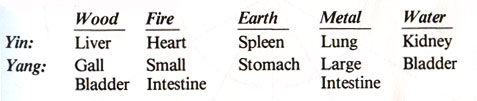

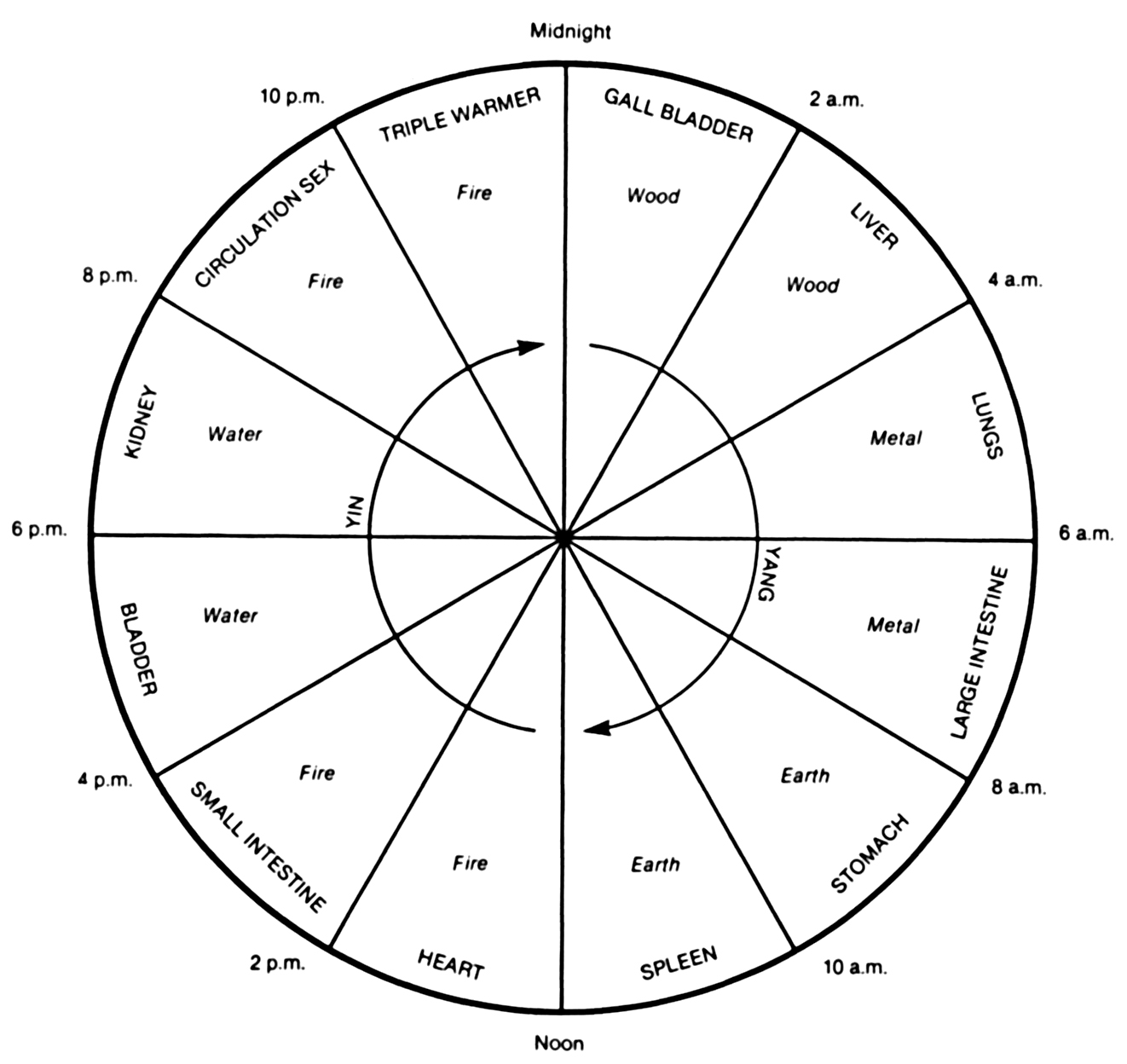

The aim of wing chun kung fu training is to develop physical, mental and spiritual awareness. These elements transcend to a higher level of life.

The aim of wing chun kung fu training is to develop physical, mental and spiritual awareness. These elements transcend to a higher level of life.

To learn more about chi power in wing chun kung fu training, be sure to read How to Develop Chi Power by William Cheung. In addition to further discussion of human pressure points and meridians, wing chun kung fu training master William Cheung will show you basic arm movements, a form to improve your chi power and chi sao exercises to engage your opponent’s chi. Permalink:

To learn more about chi power in wing chun kung fu training, be sure to read How to Develop Chi Power by William Cheung. In addition to further discussion of human pressure points and meridians, wing chun kung fu training master William Cheung will show you basic arm movements, a form to improve your chi power and chi sao exercises to engage your opponent’s chi. Permalink:

In 1966, karate legend Joe Lewis rocketed to stardom by winning Jhoon Rhee’s U.S. Nationals in Washington, D.C. Incredibly, it was his first tournament, and he won every single point with only one technique — the side kick.

In 1966, karate legend Joe Lewis rocketed to stardom by winning Jhoon Rhee’s U.S. Nationals in Washington, D.C. Incredibly, it was his first tournament, and he won every single point with only one technique — the side kick.

“There was a corridor that consisted of 108 wooden dummies representing 108 different attacking techniques,” says wing chun training expert and Black Belt Hall of Fame member William Cheung. “The monks would move down the hall and practice their defenses and counterattacks on them.”

“There was a corridor that consisted of 108 wooden dummies representing 108 different attacking techniques,” says wing chun training expert and Black Belt Hall of Fame member William Cheung. “The monks would move down the hall and practice their defenses and counterattacks on them.” Eric Oram is a freelance writer and senior disciple of William Cheung. He has taught wing chun for two decades. When he is not engaged in wing chun training, teaching or writing, he works as an actor and fight choreographer. To contact

Eric Oram is a freelance writer and senior disciple of William Cheung. He has taught wing chun for two decades. When he is not engaged in wing chun training, teaching or writing, he works as an actor and fight choreographer. To contact To learn more wing chun techniques from William Cheung, check out Wing Chun Kung Fu. In this five-DVD set, William Cheung — a student of Yip Man, a longtime friend of Bruce Lee and a member of the Black Belt Hall of Fame — demonstrates wooden-dummy exercises, empty-hand forms, reflex training, chi sao drills and more!

To learn more wing chun techniques from William Cheung, check out Wing Chun Kung Fu. In this five-DVD set, William Cheung — a student of Yip Man, a longtime friend of Bruce Lee and a member of the Black Belt Hall of Fame — demonstrates wooden-dummy exercises, empty-hand forms, reflex training, chi sao drills and more!